Bombs

Sepon is a small town about fourty kilometers from the Lao/Vietnam

border. When I stop for the night, the first people I meet at the

tiny guesthouse are Saengmonee and Khonsavanh, who are interpreters for

Handicap International, a Beligian NGO which helps the Lao clear unexploded

ordinance from various provinces in Lao. I join them for a game of

rattanball. A woven ball of rattan reed is kicked around on a netted

court similar to a volleyball game. When they take it easy on me, I'm able

to fake it. But when warmed up, they start warning me, "watch out, I'm

going to roll over." The ball is set, lobbed gently above and near the net

and in a sudden explosion of motion the player is twisting airborne in a

spinning jumpkick and the heretofore innocent sphere becomes a blur which

humms down to kick up a puff of dust on the hardpacked court as it spins

off thwack into the fence. This ain't hackey sack.

I learn how to eat Lao food at the best restaurant in Sepon,

rolling up balls of sticky rice with my hands and dunking them into soups

and spicy stews of chicken, fish and vegetables. I'm teased for my

inepetitude. "You eat like an excavator." Saengmonee is 26, and his wife

is 18. As he explains it, the difference in age is no problem in Lao, as

long as the bride's parents agree to the marriage. His invocation of a Lao

saying, "old buffalo likes to eat young grass," which I find hilarious in

its own right, later gets a second wind when I learn that buffalo is also

slang for penis.

The next morning, beautiful Mrs. Bohapahn with her smiling eyes

teaches me how to count and say "bicycle". My language lesson at the best

resaurant in Sepon brings peals of delighted laughter and the occasional

amused onlooker. Afterwards, I find myself in a truck with Tony West, the

District Coordinator for HI. The interpreters have asked him to give me a

tour.

We visit the site of a new school. Under the direction of two

Nepali Gurkhas, a couple dozen Lao men methodically sweep the ground with

metal detectors. Digging up each rusty bedspring, piece of schrapnel and

old bicycle handlebar that activates the detector makes for slow process.

The area next to the school site is not cordoned off. The villagers won't

allow the miners to clear it because they don't want holes in their soccer

field.

As we drive to a nearby village, Tony gives me some background.

Sepon is the place where tourists (a couple each week) stay when they want

to see the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The wide spot in the forest where local

guides bring them may be an oversimplification. Sepon sits in an area

which is a topographically obvious route through the mountainous terrain of

western Lao. It is likely that the Ho Chi Minh Trail wandered along

multiple routes through the region, a fact not lost on the Americans at the

time. During the late 60's and early 70's, they looked at maps of the

region and decided to bomb the shit out of it. B-52's saturation bombed

the areas deemed most likely to shelter the steady stream of people and

equipment heading to South Vietnam.

Along with a painfully large population of people missing limbs,

the legacy of this destruction remains in the huge amount of unexploded

ordinance.

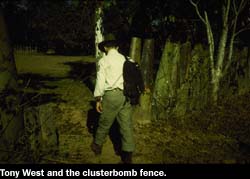

The remains of cluster bombs are ubiquitous. These two meter-long

bombs containing five hundred fist-sized bomblets or bombees were designed

to open at a certain altitude, spreading their contents. The bombees come

in many flavors. Some explode on impact. Some have a timer activated on

impact with the ground. Some won't explode until moved, and often come in

pretty colors so children will play with them. We saw live bomblets set

out of the way in tree limbs for lack of a better place to dispose of them.

Khonsavahn told of finding one imbedded in a dirt road, its exposed

surface polished by the tires of passing trucks. Tony showed me an

indication of the intensity of bombing around the village. A monk had

asked local children to bring him these casings. They constructed a fence

around his wat made entirely of hundreds of cluster bomb casings pounded

into the ground. The monk died long ago, and the villagers now avoid the

site. They interpret the monk's sense of irony as insanity.

The casualty rate from UXO accidents has dropped off sharply in the

years following 1975. Tony attributes this not to a removal of all the

UXO, but to a grisly learning curve. Trial and error has taught the people

what they can move and how. The lessons are imperfect, however, as the few

Sepon is a small town about fourty kilometers from the Lao/Vietnam

border. When I stop for the night, the first people I meet at the

tiny guesthouse are Saengmonee and Khonsavanh, who are interpreters for

Handicap International, a Beligian NGO which helps the Lao clear unexploded

ordinance from various provinces in Lao. I join them for a game of

rattanball. A woven ball of rattan reed is kicked around on a netted

court similar to a volleyball game. When they take it easy on me, I'm able

to fake it. But when warmed up, they start warning me, "watch out, I'm

going to roll over." The ball is set, lobbed gently above and near the net

and in a sudden explosion of motion the player is twisting airborne in a

spinning jumpkick and the heretofore innocent sphere becomes a blur which

humms down to kick up a puff of dust on the hardpacked court as it spins

off thwack into the fence. This ain't hackey sack.

I learn how to eat Lao food at the best restaurant in Sepon,

rolling up balls of sticky rice with my hands and dunking them into soups

and spicy stews of chicken, fish and vegetables. I'm teased for my

inepetitude. "You eat like an excavator." Saengmonee is 26, and his wife

is 18. As he explains it, the difference in age is no problem in Lao, as

long as the bride's parents agree to the marriage. His invocation of a Lao

saying, "old buffalo likes to eat young grass," which I find hilarious in

its own right, later gets a second wind when I learn that buffalo is also

slang for penis.

The next morning, beautiful Mrs. Bohapahn with her smiling eyes

teaches me how to count and say "bicycle". My language lesson at the best

resaurant in Sepon brings peals of delighted laughter and the occasional

amused onlooker. Afterwards, I find myself in a truck with Tony West, the

District Coordinator for HI. The interpreters have asked him to give me a

tour.

We visit the site of a new school. Under the direction of two

Nepali Gurkhas, a couple dozen Lao men methodically sweep the ground with

metal detectors. Digging up each rusty bedspring, piece of schrapnel and

old bicycle handlebar that activates the detector makes for slow process.

The area next to the school site is not cordoned off. The villagers won't

allow the miners to clear it because they don't want holes in their soccer

field.

As we drive to a nearby village, Tony gives me some background.

Sepon is the place where tourists (a couple each week) stay when they want

to see the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The wide spot in the forest where local

guides bring them may be an oversimplification. Sepon sits in an area

which is a topographically obvious route through the mountainous terrain of

western Lao. It is likely that the Ho Chi Minh Trail wandered along

multiple routes through the region, a fact not lost on the Americans at the

time. During the late 60's and early 70's, they looked at maps of the

region and decided to bomb the shit out of it. B-52's saturation bombed

the areas deemed most likely to shelter the steady stream of people and

equipment heading to South Vietnam.

Along with a painfully large population of people missing limbs,

the legacy of this destruction remains in the huge amount of unexploded

ordinance.

The remains of cluster bombs are ubiquitous. These two meter-long

bombs containing five hundred fist-sized bomblets or bombees were designed

to open at a certain altitude, spreading their contents. The bombees come

in many flavors. Some explode on impact. Some have a timer activated on

impact with the ground. Some won't explode until moved, and often come in

pretty colors so children will play with them. We saw live bomblets set

out of the way in tree limbs for lack of a better place to dispose of them.

Khonsavahn told of finding one imbedded in a dirt road, its exposed

surface polished by the tires of passing trucks. Tony showed me an

indication of the intensity of bombing around the village. A monk had

asked local children to bring him these casings. They constructed a fence

around his wat made entirely of hundreds of cluster bomb casings pounded

into the ground. The monk died long ago, and the villagers now avoid the

site. They interpret the monk's sense of irony as insanity.

The casualty rate from UXO accidents has dropped off sharply in the

years following 1975. Tony attributes this not to a removal of all the

UXO, but to a grisly learning curve. Trial and error has taught the people

what they can move and how. The lessons are imperfect, however, as the few

dozen annual injuries attest. Almost admiringly, for he is a military man,

Tony shows me the local scrap merchant's trove. Bomb casings have been

sawed open and the explosive burned out. The aluminum tailpieces from

bombs are rare. One of these pieces, which screws right off the steel

bombshell, can fetch ten or twenty dollars. One of the reasons that downed

aircraft were often difficult to find in Lao is that within a week of a

crash locals had cut it up and carted it away for sale.

Every house in the area has tokens of the usefulness of the

Americans' gifts from the sky. I spot anvils made of bombshells, canoes

made from the long-range dropoff fuel tanks of B-52's, troughs for pig

slop, flowerpots.

Wandering through the village, I am mesmerized by the tangible

reflection of my national guilt. As we walk to the gleaming white 4X4, a

group of children answers my smile with stares. At times like these it

does not feel good to be American.

Riding away from Sepon on New Year's Eve, I put Nustrat on the

walkman to remove myself from the scene I pass through. Hammering along

the dirt road, I find myself laughing to choke down the tears which track

through the red dust covering my cheeks.

dozen annual injuries attest. Almost admiringly, for he is a military man,

Tony shows me the local scrap merchant's trove. Bomb casings have been

sawed open and the explosive burned out. The aluminum tailpieces from

bombs are rare. One of these pieces, which screws right off the steel

bombshell, can fetch ten or twenty dollars. One of the reasons that downed

aircraft were often difficult to find in Lao is that within a week of a

crash locals had cut it up and carted it away for sale.

Every house in the area has tokens of the usefulness of the

Americans' gifts from the sky. I spot anvils made of bombshells, canoes

made from the long-range dropoff fuel tanks of B-52's, troughs for pig

slop, flowerpots.

Wandering through the village, I am mesmerized by the tangible

reflection of my national guilt. As we walk to the gleaming white 4X4, a

group of children answers my smile with stares. At times like these it

does not feel good to be American.

Riding away from Sepon on New Year's Eve, I put Nustrat on the

walkman to remove myself from the scene I pass through. Hammering along

the dirt road, I find myself laughing to choke down the tears which track

through the red dust covering my cheeks.

|

dozen annual injuries attest. Almost admiringly, for he is a military man,

Tony shows me the local scrap merchant's trove. Bomb casings have been

sawed open and the explosive burned out. The aluminum tailpieces from

bombs are rare. One of these pieces, which screws right off the steel

bombshell, can fetch ten or twenty dollars. One of the reasons that downed

aircraft were often difficult to find in Lao is that within a week of a

crash locals had cut it up and carted it away for sale.

dozen annual injuries attest. Almost admiringly, for he is a military man,

Tony shows me the local scrap merchant's trove. Bomb casings have been

sawed open and the explosive burned out. The aluminum tailpieces from

bombs are rare. One of these pieces, which screws right off the steel

bombshell, can fetch ten or twenty dollars. One of the reasons that downed

aircraft were often difficult to find in Lao is that within a week of a

crash locals had cut it up and carted it away for sale.